KNOTS blogger |

- Urban Myths and Rural Futures for Africa’s Young People

- Young people and agrifood in Africa: is it time for some good old fashioned planning?

- 2012 Call for Proposals: Grant Awards for Global Environmental Change Research in Africa

- WHAT HAPPENED TO BIOTECH IN BANGALORE?

- GETTING HOTTER: REGULATING BIOTECHNOLOGY IN INDIA

- BIOTECH BUSINESS IN BANGALORE: A DECADE OF HYPE AND HOPE

| Urban Myths and Rural Futures for Africa’s Young People Posted: 24 Feb 2012 04:20 AM PST Are people in Africa really moving en masse in one direction - into towns and cities, - as commonly believed? There are more young people in the African population than ever before – approximately 70% of Africa's one billion people is under the age of 30. Furthermore, continuing a long-term trend, many rural youths are reportedly choosing not to pursue livelihoods in the agriculture sector, especially as farmers. This story of young people apparently turning their back on farming forms a compelling narrative that is linked to others around de-agrarianisation in rural Africa and of entrenched, high and rising youth unemployment. The argument goes that the future for most young people lies not on the farm or even in agriculture, but in new jobs and new sectors in Africa's burgeoning towns and cities. |

| Young people and agrifood in Africa: is it time for some good old fashioned planning? Posted: 24 Feb 2012 03:47 AM PST  Photo: Pakalinding farmers, The Gambia by gerrypops on Flickr Has anyone yet properly analysed the human resources that will be needed in the agricultural sector in Africa in 10 or 15 years? And if not, why not? Let me explain. If a government concludes that over a given planning horizon there will likely be a shortage of secondary school teachers, it might create additional incentives (bursaries, one-off grants etc) to attract young graduates to a one-year teacher training course. Similarly, if a manufacturing sector expects that a shortage of qualified engineers will hinder its future competitiveness, it might push government to expand the teaching capabilities of university engineering departments and then work to make engineering a more attractive career choice in the eyes of young people. |

| 2012 Call for Proposals: Grant Awards for Global Environmental Change Research in Africa Posted: 24 Feb 2012 03:33 AM PST START's 2011 Grants for Global Environmental Change (GEC) Research in Africa are one-year projects in support of science-based research to build the capacity of individual scientists and their affiliated institutions in Africa. |

| WHAT HAPPENED TO BIOTECH IN BANGALORE? Posted: 24 Feb 2012 01:53 AM PST A decade ago, biotechnology was being hyped as the next big thing in Bangalore, India. Building on the successes of the IT sector, BT (biotech) was, it was argued, going to provide a platform for growth, innovation, job creation and more. So what happened next? A recent seminar (programme here) jointly convened by the Centre for Public Policy at the Indian Institute of Management in Bangalore, the Association for Biotechnology Led Enterprises and the STEPS Centre, and supported by UKIERI, explored this question. Debates focused on the trajectory of biotech businesses and the challenges of regulating biotechnology. This work builds on the long-running work by STEPS Centre members on the politics of policy surrounding biotechnology across the world. Ian Scoones, STEPS Centre director, who was at the workshop, has written some longer pieces about the issues (see below). Related posts by Ian Scoones

Links |

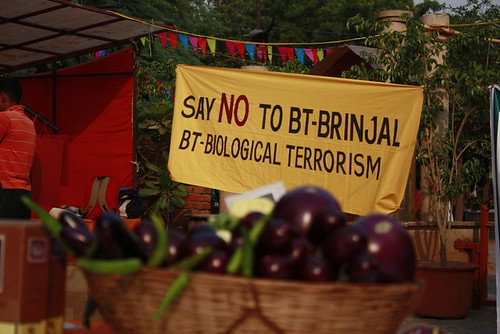

| GETTING HOTTER: REGULATING BIOTECHNOLOGY IN INDIA Posted: 24 Feb 2012 01:48 AM PST by Ian Scoones, STEPS Centre co-director Biotechnology offers many potentials but also dangers. Regulation is clearly essential. But how, over what and with what measures is less clear. The debate about how to regulate emerging technologies associated with biotechnology is a hot one the world over. In India, it's about to become much hotter.  Photo: No to Bt Brinjal, from joeathialy on Flickr In July 2011, the Biotechnology Regulatory Authority of India (BRAI) Bill (pdf link) was presented by the minister of science and technology to parliament. It has been long in the making, building on a series of commissions – on agriculture and health – led by Professors Swaminathan and Mashelkar in 2004 and 2005. The proposals contained in the Bill were the subject of a panel discussion at the recent seminar jointly convened by the Centre for Public Policy at the Indian Institute of Management in Bangalore, the Association for Biotechnology Led Enterprises and the STEPS Centre, and supported by UKIERI. Everyone agrees that biotech regulation in India needs an overhaul. There are too many overlapping responsibilities, unclear mandates and lots of red tape. Regulatory delays result in losses of revenues for businesses, and the lack of transparency and unclear procedures are frustrating for applicants and opponents alike. The debacle over Bt brinjal (aubergine/egg plant), which dominated the headlines in 2010, illustrated the limits of the current system, with conflicting scientific reports and mismanagement of the process by the GEAC (Genetic Engineering Approval Committee). An independent authority with a clear mandate and streamlined procedures was supposed to get over the chaos and confusion that has dominated the regulatory scene in the past years. But will the BRAI achieve this? Some argue that self-regulation and industry oversight is all that is needed. A light-touch approval process would speed up innovation, and allow Indian biotech to flourish. Surely, the regulation-sceptics argue, India can make use of regulatory approvals elsewhere in the world, and not get mired in repeat assessments locally. GM crops are often cited as an example. If Americans can eat Bt foods, why not Indians? they argue. Equivalence and harmonisation should characterise an internationalised regulatory system, with simplicity and efficiency as the watchwords. No-one at the seminar argued this way, however (although there are still plenty who do). Instead, seminar presenters argued that regulation is essential. Vijay Chandru (Strand Life Sciences) argued that the "genie is out of the bottle". Biotechnology is massively powerful, but also potentially hugely dangerous, he said. We are only on the cusp of realising some of its potentials, with sequencing times reducing dramatically and costs halving every five months. The initial sequencing of the human genome cost $2.7bn, while today it can be done for about $1000, he claimed. Before long, what he dubbed "home-brew DIY genomics" will be possible, with DNA printers able to reveal full human gene sequences for a few hundred dollars. "There are obvious dangers", he observed. Take synthetic biology – new organisms including lethal viruses could be manufactured. "We really need to have a good regulatory process in place", he noted. "And we need to do it soon, or there will be all kinds of chaos". So what are the key ingredients of a regulatory system? Efficiency and cutting down on red-tape is important for sure. And so is the sort of expert "domain knowledge", emphasised by Ravi Kumar (XCyton). Good information, based on solid science, outlining all the uncertainties is essential, he argued. Avoiding what he termed "the agony of local clearance" was a must. A "clean slate" was needed, he said, as "the current system is just not working". But for regulation to have purchase, and to be regarded as legitimate and authoritative, it must also be trusted. An "all powerful" institution, no matter what its high-sounding aims are at the beginning, will, Ravi Kumar argued, be corrupted in time. Today, he commented, "we suspect every institution and its integrity". The lack of faith in public regulatory institutions is of course not just an Indian experience. This has happened in Europe and elsewhere. Rebuilding trust is essential. And the global lessons suggest that this requires a solid commitment to public participation and democratic accountability. As the seminar discussed, it is on these issues in particular that the BRAI proposals remain severely lacking. Leo Saldhana (Environment Support Group) presented the results of a comprehensive critique of the Bill he undertook with his colleague, Bhargavi Rao. The critique is damning on a number of fronts. The proposed BRAI is seen to centralise authority; mix sector promotion with regulation, creating a conflict of interest; be democratically unaccountable, failing to recognise the multiple tiers of government; be excessively reliant on narrow technocratic expertise; override other important legislation (including the Right to Information Act); and ignore public concerns, making objection and protest impossible. Their recommendation is that the Bill is potentially unconstitutional and should be rejected. The paper provides the details, but the panel and plenary discussion that ensued concurred that "a major rethink is required". Vijay Chandru suggested that an alternative "marked up" version of the Bill be produced, and submitted to Parliament. Like so many other attempts to streamline regulation in favour of industry interests in order to promote efficiency and growth, the BRAI Bill appears to fall into the same traps. It assumes that democratic deliberation on alternatives, and the risks and costs of each, represents an inefficient 'bottle-neck', rather than a necessary way of creating public legitimacy for regulatory decisions. It sees only one narrow form of expertise as necessary, rather than a more inclusive approach that recognises diverse, plural views, including those of the public. It frames the response in terms of 'risk', assuming that probability of outcomes are known and can be managed technocratically through expert decision-making, rather than recognising uncertainty or deeper ignorance as the norm. Under such situations, a precautionary approach is required, which acknowledges we often don't know what we don't know - especially when the "genie is out of the bottle". It creates unaccountable governance arrangements that actively exclude public participation, which is seen as a time-wasting diversion from the important priorities of growth and economic progress. But in a vibrantly democratic country like India, avoiding public debate, as the experience of the past decade has shown, is not an option. Inclusion, participation, accountability and democracy must be central to any regulatory system. Many at the seminar agreed that a top-down, elitist, technocratic, expert led system will not, in the end, serve industry or the public well. The dilemmas are well illustrated by the regulatory debate surrounding Bt brinjal (genetically modified aubergine) which exploded during 2010. Public disquiet about the first GM food crop was heightened by the fact that brinjal is a widely used vegetable, of significant cultural and biodiversity importance. Scientists too were divided on the interpretation of the safety tests, and, as ever, Monsanto mishandled the public relations fomenting media debate and public concern. The then minister, Jairam Ramesh, decided that public involvement was vital, and hosted a series of well-attended 'town hall' debates across the country. Some dismissed these are populist political theatre, captured by an elite middle class group of environmentalists and campaigners, who did not have the views of farmers in mind. Others regarded this move as a brave shift to wrest the control of the regulatory process from a scientific elite, captured by industry. In reality it was probably a bit of both; but the overall outcome was important, not only for the specific Bt brinjal case, but for Indian biotechnology regulation overall. Minister Ramesh provided a statement in February 2010 "in order to ensure complete transparency and public accountability": "...it is my duty to adopt a cautious, precautionary principle-based approach and impose a moratorium on the release of Bt-brinjal, till such time independent scientific studies establish, to the satisfaction of both the public and professionals, the safety of the product from the point of view of its long-term impact.... " Here two important moves are made by the Minister. He argues for a precautionary approach, accepting uncertainty, and he argues that publics must be involved in assessing the evidence. Both these principles are essential for any regulation of any technology where risks are real but also uncertain. It appears that the BRAI Bill has not taken on board these lessons, but it would be wise to do so. It is to be hoped that the democratic deliberations in the Indian parliament, as well as any of the legal challenges which will undoubtedly follow, will help to create the appropriate revisions to make a more effective, democratic and accountable regulatory system for Indian biotechnology. This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| BIOTECH BUSINESS IN BANGALORE: A DECADE OF HYPE AND HOPE Posted: 24 Feb 2012 01:30 AM PST By Ian Scoones, STEPS Centre co-director A decade ago, biotechnology was being hyped as the next big thing. Building on the successes of the IT sector, BT (biotech) was, it was argued, going to provide a platform for growth, innovation, job creation and more. So what happened next?  Picture: BT cotton, by nostri-imago on Flickr. A recent seminar jointly convened by the Centre for Public Policy at the Indian Institute of Management in Bangalore, the Association for Biotechnology Led Enterprises and the STEPS Centre, and supported by UKIERI, explored this question. Certainly the hype around biotechnology has not gone away. The Karnataka State Government's website proclaims: "Karnataka has emerged as an undisputed investment destination for investors worldwide, offering vast business opportunities across sectors....Its capital, Bangalore, now a global brand has the largest biotechnology cluster in India, aptly named as Biotech Capital of India. Bangalore has sky-rocketed into the new millennium. A pulsating megapolis, a haven to IT-BT and Fortune -500 companies and today the world's most preferred investment destination". But what are the realities behind the spin? At the seminar, Ian Scoones (STEPS Centre) reflected on some of the changes over the past decade since he carried out research on the emerging biotech sector. Across India the sector has certainly grown. According to the Biospectrum-ABLE survey of 2011, it crossed the $4bn revenue mark. But it did not grow as fast as expected, nor create as many jobs. The 'big hit' patents promised a decade ago as part of the pipelines of the start-ups did not materialise, and regulatory challenges have continued to plague the industry. That said, some important successes have been recorded. Biocon, the flagship biotech company in Bangalore led by Kiran Muzumdar Shaw, has gone from strength to strength. A massively oversubscribed flotation in 2004, has led to year on year growth since. Overall, the biotech sector has grown around 20% each year, even through the global downturn of the late 2000s. A comparison of the 'top 15' companies (see slide 11 of Ian Scoones' presentation) by total revenue in the sector in 2003-04 and 2010-11 shows a dominance of home-grown companies. A noticeable trend has been the growth of the agri-biotech sector. A decade ago, Bt cotton was formally released by Monsanto-Mayhco, and has since expanded on a massive scale, with a whole array of companies taking on the proprietary genetics and incorporating it into their germplasm. The result is that in 2010-11, a third of the 'top 15' biotech companies in India are trading Bt cotton. However, with a few exceptions (perhaps only Biocon, Serum Institute and Panacea Biotec), most biotech companies remain small, dependent on external alliances, and in the case of agri-biotech almost completely reliant on Monsanto's Bt technology. So what happened to the discovery and innovation model that was touted in 2002, whereby local companies would grow on the basis of new technologies, fostered through R and D investment? This has happened in important areas, however, the big breakthroughs have not emerged. As Vijay Chandru (Strand Life Sciences and ABLE) put it "There has been no second Biocon". Why is this? Is the Bangalore biotech innovation system somehow deficient, or is this a normal pattern, reflected elsewhere in the world? The seminar discussion reflected on this. Certainly in the US, the biotech sector is dominated by a few big companies, with many others supporting these in a highly dynamic, fast-turnover setting. Technology clusters are supposed to be the drivers of growth, drawing on geographical synergies, links to academic establishments and strategic state investments. Has this happened in India? In India, clusters have emerged – in Bangalore, Hyderabad, Mumbai, Pune and elsewhere – but how dynamic have they been? Participants at the seminar suggested that it is taking time for such clusters to mature, and that distinct comparative advantages are only now being found. There were mixed views on the benefits of competition between clusters – say between Bangalore and Hyderabad – and a sense that the full advantage of proximity to top-rank scientific institutions was not being realised. Indeed, one of the big selling points of Bangalore as a biotech destination has always been the presence of the prestigious Indian Institute of Science and the National Centre for Biological Sciences, along with whole host of engineering and technology colleges. Top flight scientific expertise in the biological, information and engineering sciences should, so the theory goes, result in greater innovation capacity. While moves have been made at IISc, NCBS and elsewhere to link basic science with commercial applications, this has only influenced the culture and practice of science in such institutions at the margins over the past decade, and the links between science and business remain weak. And what about the application of science for development? With the science-business model being influenced by funding flows, patent ownership and market control, the opportunity of biotech businesses to develop technologies responding to the massive local needs of poverty, ill-health, poor environmental conditions, agrarian distress and so on remain structurally limited. The Prime Minister, Manmohan Singh, argued at the Indian Science Congress in January 2012 needs to begin "grappling with the challenges of poverty and development". He continued:"It is said that science is often preoccupied with problems of the rich, ignoring the enormous and in many ways more challenging problems of the poor and the underprivileged". Innovation, he argued, should be for social benefit, not just for profit. These are fine words. They are often repeated in the Indian context where poverty and inequality continue to grow, while the GDP shows 7% (or more) growth rates. In India, there is a vast demand for low-cost, appropriate biotechnologies in India, and many of those at the 'bottom of the pyramid' can increasingly afford them. A growing middle class also has new demands – there are, it was noted, 50m diabetics in India. However, the current structure of the biotech industry, with some notable exceptions, cannot respond to these demands. The patents are held by the big companies, the financing is geared to northern markets, and the technological and business capacities are influenced by a US/European model. So what new 'inclusive' innovations exist? As Ravi Kumar from XCyton explained, medical diagnostics is an important growth area, improving the effectiveness of public health responses, and reducing patient costs. The potentials of portable PCR kits for diagnostics in rural health care are significant, for example. Equally, as Vijay Chandru pointed out, there are growing potentials in the field of 'biosimilars' (off-patent generic biological compounds). Low cost production of important pharma products may well open up, Chirantan Chatterjee (IIM-B) explained, as hundreds of important products are released from patent restrictions in the next few years. The market in biologics is estimated to be around $270bn, with huge potentials for the development low cost alternatives. Indeed, as Vijay Chandru observed, while 'Brand India' (and perhaps particularly Bangalore) is dominated by the IT sector, perhaps the greatest global contribution in the technology field over the past few decades has been the development and supply of low-cost generic drugs to the world. How then can a more appropriately Indian biotech sector emerge? There has been much talk of state support and investment, the 'midwifery' that Peter Evans talks of. But has state support been well directed over the last decade? Most believe it hasn't. The Bangalore Helix Biotech Park has been plagued by controversy, and has only just got off the ground. State support for early financing has improved, but what about the next-stage financing?, participants asked. In a complex industry like biotech, returns are often slow and uncertain. The parallels with IT and the software development successes of Infosys, Wipro and the rest are inappropriate, it was argued. While there has been renewed interest in 'state capitalism' because of the models of China and Brazil, Bangalore has long had a tradition of state support to emergent industries. The Dewan of Mysore, Ishmael Mizra, commented in 1926: "We in Mysore have always been alive to the economic functions of government and have endeavoured, where there was any practical hope of success, to aid and encourage the growth and the starting of new enterprises by private capitalists and in special cases to undertake their complete management. The main objective has been, not merely to increase the wealth of the state, but to provide the technical ability and business acumen which form so important a part of the nation's wealth". Biotech in Bangalore retains the hype and much of the hope of a decade ago. Today, however, commentators are more sanguine about the potentials. The sector is clearly thriving, but in a different way to what was envisaged. As Chirantan Chatterjee explained, more hybrid science-business models are emerging which switch between innovation/discovery and generics imitation/contract research. This may be a more realistic expectation, and one that can capture the potentials of biosimilars production, genomics-based diagnostics and more. However, direction of innovation remains a concern, as well as the diversity of applications and the distribution of benefits. The seminar concluded that much more could be done by states and the union government to build the industry, incentivise entrepreneurs, foster links with the diaspora, forge links between science, engineering and management training, protect and support emerging companies, and direct innovation towards the principles that the Prime Minister talks about - inclusivity, poverty reduction and sustainability. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from KNOTS blogger To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |